QAnon, fan fiction, and the blurry line between reality and fantasy

The conspiracy theory owes its success to Harry Potter as much as 4chan and Facebook. What can it tell us about the future of conspiratorial thinking?

Illustration: Emily Thiang/iStock

In 2019, the writer and researcher Tim Hwang proposed a spinoff to National Novel Writing Month (also known as NaNoWriMo) that would focus on what he saw as an increasingly vibrant literary tradition: conspiracy. Instead of dedicating a month to pumping out an entire novel at unreasonable speed, participants would be tasked with producing a viable conspiracy theory explaining some aspect of human affairs.

“For better or for worse (frequently the worse), the genre of conspiracy includes some of the most narratively ambitious, memetically successful, and potent oral traditions of modern American life,” Hwang wrote in a Medium post explaining the appropriately named NaCoWriMo. “Conspiracy theory is a uniquely powerful species of fan fiction about reality, one whose fandoms are capable of creating massive change.”

Hwang’s project might have been a humorous diversion, but it strikes at something potent: conspiracy theory is ultimately about storytelling. And, like other kinds of storytelling, it can be an earnest attempt to make sense of a messy shared reality.

The world we live in is complicated, and simple cause and effect are often obscured by happenstance, confusion, inexplicability, and—yes—actual, honest to God conspiracy. Those who indulge in conspiratorial thinking are usually trying to establish a coherent narrative from disparate parts and knowledge, or trying to rationalise an unpleasant truth by filling in the gaps. Often, that takes a bit of creativity.

Conspiracy theory is not new, and even its more modern expressions have older antecedents. In his famous 1964 Harpers essay ‘The Paranoid Style in American Politics’, the historian Richard Hofstadter described a current of “heated exaggeration, suspiciousness, and conspiratorial fantasy” that had defined American political thought from its earliest stages, in the minds of the elite and the dispossessed alike.

But it’s also difficult to deny that the internet—and particularly the social web of the 2010s—has enormously changed the character of conspiracism and how it is expressed. Indeed, there’s good reason to believe that the deep vibrational frequencies of American politics have been transferred globally thanks to the internet and the US companies that dominate it, bringing the paranoid style along for the ride. Anyone who pays attention to Australian political life will undoubtedly notice that if something crops up in the fever swamp of the American public sphere, it will eventually find its way here in degraded, barely adapted form.

Reading through the millions of posts, QAnon looks more like the world’s largest collective fiction project in desperate need of an editor.

The coronavirus pandemic has amplified this trend. The mysterious, deadly pathogen and the iron-fisted public health measures deployed to contain it virtually invite conspiratorial interpretations, which have ranged from the plausible to the farfetched. At the same time, efforts to slow the virus’s spread have forced a significant portion of the world’s population to live even more of their lives online. When grounded interpersonal contact is replaced with a digital substitute and parasocial online relationships, the novel (and often irrational) explanations offered by conspiratorial thinking become all the more inviting. A quick tour through the comments section of any news story about COVID-19 makes that abundantly clear.

In an essay for the Journal of Design and Science at MIT scholar and internet activist Ethan Zuckerman describes “the Unreal”: a form of politics that “forsakes interpretation of a common set of facts in favour of creating closed universes of mutually reinforcing facts and interpretations”. The idea that our shared reality might be subjective obviously isn’t new; philosophers have grappled with it for millennia. But there’s an appeal in the creation and maintenance of these “closed universes” which is all too familiar to the writer or reader of fiction.

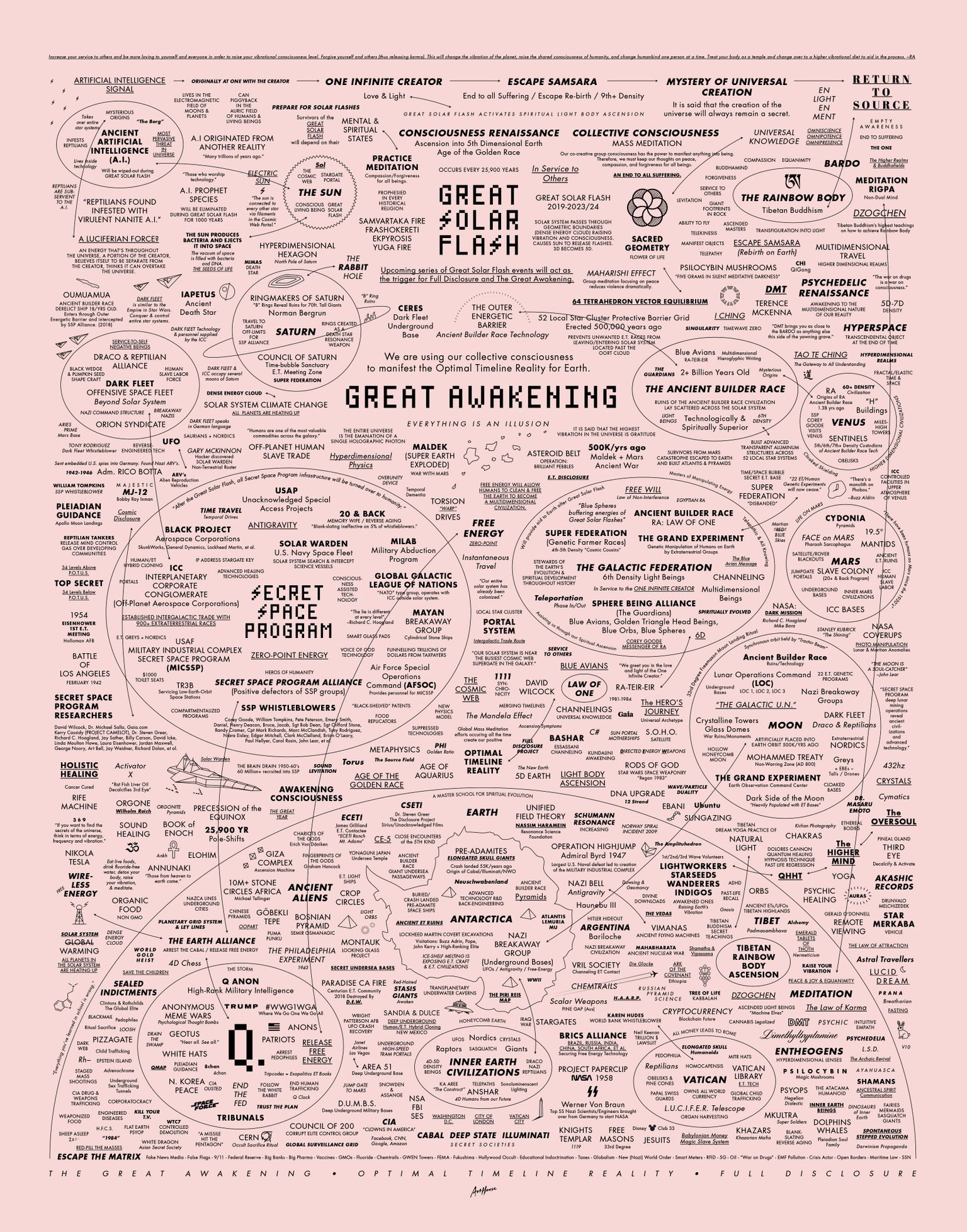

It’s impossible to write about online conspiracy and its fictional quality without considering QAnon, the “big tent” conspiracy theory that has warped and disfigured the political landscape since it emerged in 2017. What started as the simple story of Donald Trump’s secret quest to obliterate a deep state of elite, devil-worshipping pedophiles has sprawled out into an all-encompassing, open-source Theory of Everything; a narrative engine into which followers can integrate any number of personal fixations—from wellness culture and green politics to fantasies of subterranean lizard people and UFOs. It has taken off over the traditional subjects of conspiratorial interest like the Illuminati or the Bilderberg Group because it is, by its very design, so accommodating. If you want to spin your own narrative thread integrating the Illuminati into the QAnon mythology, you can—and you might just pick up a few followers doing it.

The sheer flexibility of its story framework is best represented by the Great Awakening map, a widely shared image (now available in poster form) described by its creator as “the supreme red-pill navigational chart for escaping The Matrix and returning to source”. It situates QAnon amid a vast field of interlocking conspiracies—some commonly repeated, others more esoteric—creating something that looks like the Marvel Cinematic Universe of paranoia.

Image courtesy Art House 5D Shop

Overcomplicated and feverish as it may be in its late stages, QAnon is undeniably compelling as a narrative. It contains everything you’d want in a great story: epic scope, a huge cast of characters, a battle between good and evil, a hero’s journey, endless court intrigue and the dual promise of salvation for the righteous and punishment for the wicked. It’s unsurprising that, when presented with the endless complexity and relentless atomisation of modern life, someone might be more inclined to immerse themselves in a postmodern fairy tale than a political system that seems broadly indifferent to the actions and desires of ordinary people.

QAnon storytelling, built around ‘drops’ posted to platforms like 4chan and 8chan by an alleged (but almost certainly fictional) senior government official with high-level security clearance, is largely generated by its own online community; a legion of self-appointed sleuths who scrutinise every piece of dubious intel for possible relevance within the larger canon. There are obvious parallels with religion or faith (some have described the work of QAnon devotees as being akin to Talmudic commentary). But reading through the millions of posts across message boards, Facebook groups and Telegram channels, it looks more like the world’s largest collective fiction project in desperate need of an editor.

QAnon has written the playbook for what the future of conspiracy theory will look like.

In part, this sense of storytelling and play comes from the fact that much of the QAnon worldview is plainly untrue and fantastical. (That is, if you believe it is implausible that Hillary Clinton was captured and executed by Donald Trump early in his presidency and replaced by a body double.) But it also owes much to the fact that that worldview is utterly totalising. Every world event and minor happening is quickly interpreted by acolytes through the existing lore, and QAnon community fame can be achieved by being the one to make those connections in a compelling and ‘viral’ way. It is strangely reminiscent of LiveJournal fan fiction of the early 2000s: based around a universal core, but with endlessly creative offshoots that interact in unusual ways and consciously cross-pollinate sources and inspirations. (You can argue forever about whether Q fans or the Harry Potter fan fiction community is more cult-like in their behaviour.)

As one of the hosts of the QAnon Anonymous podcast said: “QAnon has a canon, but the canon is basically this coded language of the drops. The tapestry of the story is done by these amateur researchers… it’s decentralised storytelling, like thousands of different fanfic threads going on at once with very little to chew on at the centre.”

Trump has left office now, and it seems that without his centrifugal energy—and the tolerance of the major social media platforms—QAnon has largely dispersed and splintered. Recent claims that Joe Biden has been living in a fake White House owned by the actor Tyler Perry notwithstanding, QAnon no longer seems to contain its early vitality, and Q has not posted in almost a year. Credible allegations that Q was actually a pair of right-wing American porn site hosts living in the Philippines, aired in both an episode of the Reply All podcast and the HBO docuseries Q: Into the Storm, no doubt knocked some of the wind out of the sails. But QAnon has written the playbook for what the future of conspiracy theory will look like: a federation of online storytellers building a simulacrum of reality on their own terms, endlessly iterating, refining and expanding the lore of those who came before them. The ease with which many of Q’s fanbase have moved onto dark theories about COVID-19 vaccines, a sinister medical establishment, and the potentially liberating effect of horse dewormer, is a testament to its fundamental flexibility.

Alan Moore, the English comics author behind iconic texts of modern paranoia V for Vendetta and Watchmen, said in a 2003 documentary that people believe in conspiracy theories because “that is more comforting”.

“The truth of the world is that it is chaotic,” he said. “The truth is that it is not the Jewish banking conspiracy or the grey aliens or the 12-foot reptiloids from another dimension that are in control. The truth is more frightening: nobody is in control. The world is rudderless.”

But that’s boring. And as many people who spend an increasing amount of their time on the internet have come to realise, they can do better.