The island of Hy-Brasil never existed. So why did it appear on maps for nearly 700 years?

What the story of the “Irish Atlantis” says about our need to make sense of an uncertain world.

Illustration by George Wylesol

Maps tend to give away how a story ends. Right now ‘You Are Here’, at the beginning. But look up the right grid coordinates, or type the right address into a satnav, and you’ll see exactly where your hero’s journey will finish.

Reaching the island of Hy-Brasil is a more complicated matter, though. It will see you first.

You’ll be sailing through familiar coastal waters when a sudden fog engulfs your ship. You’ll wait in the muffle, hearing waves slapping your ship’s bow, and the creaking of ropes and masts. Then the fog clears and you find yourself in deep, calm water, close to looming black cliffs.

You row ashore in the long shadows before twilight. As you make your way inland, the forest yields to an open meadow grazed by soft black rabbits the size of horses. In the distance you see a black stone castle and you feel relieved—this means a town, which means people. Fascinated, you draw closer to the castle, silhouetted now against the setting sun. In the doorway stands an old man with kind eyes.

The next day you return to your ship with sacks of gold and silver, head full of the old magician’s stories. You try to explain it all to your captain—the rabbits, the castle, the magician, his gift—but they vanish from your tongue as swiftly as your wages slip through your fingers at the gambling table. Your captain stows the treasure and chastises you for your fairy superstition. But your leg, the one that broke badly in a storm and never set quite right, feels stronger somehow…

Also known as Brasil, Hy-Breasal, Hy-Breasil, O’Brazil and Brazir, Hy-Brasil is named for Breasal, the mythic Irish High King. (Any similarity to the South American nation is accidental: the other Brazil got its name from conquistadors who dubbed their new territory after the continent’s blood-red native timber, brazilwood.) As early as 1325, Genoese sailing charts pinpointed Hy-Brasil somewhere off Ireland’s west coast. Over nearly seven centuries, it appeared on more than 300 nautical maps, as generations of cartographers trusted rumours and vague sightings of the island.

But as maritime traffic increased, the mapmakers wondered if they’d been hoodwinked by optical illusions, navigational errors or even deliberate hoaxes. In a 1753 map, British cartographer Thomas Jefferys hedged his bets by marking it as the “Imaginary Isle of O Brazil”. By 1873, Hy-Brasil had been mapped for the last time. It had become a phantom island: one that had never existed at all.

Except that’s not quite true. Hy-Brasil did exist, because people wanted it to. And in some ways it still does. We need destinations for our quests, terrain for our stories. Perhaps the maps simply illustrated this desire.

In many ways, the earliest maps were stories. Aboriginal songlines in Australia are paths across Country recorded as song cycles: a navigator can cross vast distances by repeating the adventures of creator-beings, which attribute cultural meanings to key landmarks. The epic poet Homer, whose Odyssey invented some of literature’s most famous islands, is credited as the founding father of Western geography.

And ever since 360 BCE, when Plato mentioned the submerged city of Atlantis in his dialogues Timaeus and Critius, generations of philosophical seekers have struggled to identify its real-life location. To Plato, the doomed Atlantis was simply an allegorical contrast to his perfect Republic; but that didn’t stop amateur historians claiming it was everywhere from Malta to Morocco.

The stories we tell are the paths we choose.

You might think it’s obvious that Plato made up Atlantis, that it was just a story. But historically, people resisted such unambiguous distinctions between truth and fiction. A place could be both—and that was what made it powerful.

In early medieval Europe, maps were treated as both real and allegorical, both religious and mythological. Theologians genuinely believed the Garden of Eden was out there somewhere, and geography treatises often included fabulous tall stories of strange phenomena called mirabilia—‘wonders’.

A new, more practical type of map was invented in the late 13th century: the portolan chart, which was designed to help sailors pilot their ships along coastlines. As Mediterranean trade moved north, portolan charts expanded to cover the British Isles and northern Europe—including Atlantic ‘islands’ such as Hy-Brasil.

Portolans are crisscrossed by multiple starbursts called windroses that represent the 16 compass directions. Navigators would use the closest windrose to plot a course to their desired destination. Perhaps the many overlapping pagan, classical, Christian and literary legends of Hy-Brasil also establish desire lines. The stories we tell are the paths we choose.

Many ancient cultures have located their afterworlds in the west, believing souls slip into paradise like the sun slips below the horizon. Irish lore came to identify Hy-Brasil as both a land of the dead and a fairy realm, which was said to emerge from a blanket of fog or rise up from below the waves once every seven years.

In the 1470s, Spanish Basque chronicler Lope García de Salazar recounted an English legend that after King Arthur’s death, his sister Morgan Le Fay laid him to rest on Hy-Brasil and “enchanted that island so no ship can find it”. Curiously, Salazar claimed that the enchantment lost its power “if the ship can see the island before the island the ship”. You’d have to sneak up on Hy-Brasil like you were playing a watery game of Statues.

Earlier, Irish adventurer-saint Brendan the Navigator starred in an absolute blockbuster of a tale by the publishing standards of the year 800—hundreds of manuscript copies still survive. In the story, St Brendan sets out westwards for the Promised Land. Huge, savage mice and vicious sea cats pick off his crew, but God sends backup in the form of giant eagles. At last Brendan arrives at a wonderful island filled with fragrant fruit trees and strewn with precious stones. An angelic old man whose entire body is covered in dove-like white feathers welcomes the rock star of the early Christian church, who grabs some fruits and jewels before heading home.

Egged on by such tales, and encouraged by the precision of Hy-Brasil’s placement on portolan maps, real people soon became determined to find the mythical island. Two expeditions set off from Bristol in 1480 and 1481, and a letter from 1487 mentions “the men from Bristol who found Hy-Brasil”. Other English gentlemen squandered their family fortunes on fruitless voyages.

To impose our satellite-mapped view upon Hy-Brasil is to succumb to a different kind of cartographic hubris.

But the island forged at least one Irishman’s fortune. In 1664, Murrough O’Ley was out walking, feeling gloomy after fighting with his wife. Without warning, several strangers bundled him into a sailboat and took him forcibly to an island they called O’Brazil. He stayed there two days before his kidnappers dumped him in Galway, “hoodwink’d” and “very desperately ill”.

Seven years later, O’Ley realised he could heal people, even though he’d never studied medicine or surgery. Hy-Brasil had made him a doctor.

O’Ley’s story was still remembered in County Galway two centuries later, though it had naturally become embroidered over time. In an 1839 version, a mysterious old man on the island had given O’Ley an enchanted book, but warned him not to open it for seven years. O’Ley obeyed, and the book duly granted him healing powers.

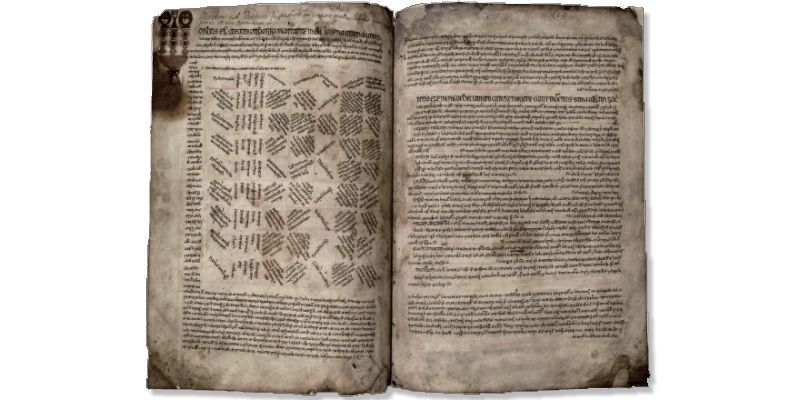

Like the maps, this book is also real. It’s a 15th-century medical manuscript, written in Irish and Latin, that translates a 12th-century Arabic text. The so-called Book of Hy-Brasil now lives at the Royal Irish Academy, which purchased it in 1844.

Image: The Book of O’Lees via the Royal Irish Academy

Image: The Book of O’Lees via the Royal Irish Academy

Cynics say O’Ley concocted his tale as a promotional stunt for his medical services, using an old family book to lure prospective patients. Others, more comfortable exposing the truth than embracing the mystery, have worked to debunk the island’s other falsehoods; modern spoilsports have even identified Hy-Brasil with Porcupine Bank, an Atlantic shoal about 200km west of Ireland that was first discovered in 1862.

But to impose our satellite-mapped view upon Hy-Brasil is to succumb to a different kind of cartographic hubris: we fool ourselves that we can, and should, solve every mystery. But the world is still in chaos, and we respond the same way the old navigators did: by creating a space for the real and the imaginary to mingle. Call it religion. Call it magic. Call it conspiracy theory. Call it literature. Hy-Brasil tantalises seekers because it’s all quest and no destination.

The story about the large black rabbits and the magician in a castle was first published by Anglo-Irish satirist Richard Head (yes, that was his real name) in a 1675 pamphlet. Head deliberately wrote it in the literary genre of ‘true history’—the most famous examples of which are Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe and Moll Flanders, two books purportedly based on real events but which stretch the notion of truth in storytelling to breaking point. In his pamphlet, Head adopted the voice of a sea captain named John Nisbet, who visited Hy-Brasil with his crew while travelling from France to Ireland.

Plenty of gullible readers have taken ‘Nisbet’ at his word. But the ‘true history’ genre gets its frisson from the possibility of truth—no matter how far-fetched. That’s why the medieval ‘wonder’ tale was more compelling for being framed as scholarly research. And it’s why Plato attributed the Atlantis story to the influential Athenian statesman Solon, who had travelled widely.

The last recorded sighting of Hy-Brasil was in 1872 by Irish antiquarian and folklorist TJ Westropp, who was then aged 12. He’d spotted the island twice before, but on this trip he’d brought along his mother, his brother Ralph and several friends to back up its existence.

“It was a clear evening,” Westropp recalled in a 1912 paper to the Royal Irish Academy, “with a fine golden sunset, when, just as the sun went down, a dark island suddenly appeared far out to sea, but not on the horizon. It had two hills, one wooded: between these, from a low plain, rose towers and curls of smoke.”

Everyone saw it. Then it vanished off the map and into its own story.